Michigan Relics: Difference between revisions

(section move) |

(photo2) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

==Pseudoarchaeology== | ==Pseudoarchaeology== | ||

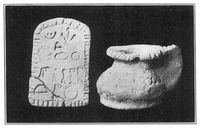

[[File:Relics2.JPG|thumb|200px|right|Michigan Relics, clay tablet and cup. <ref>Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." ''American Anthropologist'', New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf</ref>]] | |||

With the rhetoric in which they were originally presented, the "relics" supported pseduoarchaeological narratives, primarily pre-Columbian contact. With their hieroglyphic inscriptions, the discoveries supported the idea that the state of Michigan and North American in general were inhabited, or visited, by European peoples before the existence of Native American tribes in the region. The inscriptions found on the clay and copper discoveries were tied to the the Egyptian, Greek, Assyrian, Phoenician, and Hebrew alphabets, thus providing evidence that a more advanced civilization existed in the region besides the Native Americans. The inscriptions were religions in nature thus proving that this advanced civilization had knowledge of the Old Testament. <ref>Talmage, James Edward. "The Michigan Relics: A Story of Forgery and Deception." ''Deseret Museum Bulletin,'' No. 2 (1911), 6-8. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044043476324</ref> | With the rhetoric in which they were originally presented, the "relics" supported pseduoarchaeological narratives, primarily pre-Columbian contact. With their hieroglyphic inscriptions, the discoveries supported the idea that the state of Michigan and North American in general were inhabited, or visited, by European peoples before the existence of Native American tribes in the region. The inscriptions found on the clay and copper discoveries were tied to the the Egyptian, Greek, Assyrian, Phoenician, and Hebrew alphabets, thus providing evidence that a more advanced civilization existed in the region besides the Native Americans. The inscriptions were religions in nature thus proving that this advanced civilization had knowledge of the Old Testament. <ref>Talmage, James Edward. "The Michigan Relics: A Story of Forgery and Deception." ''Deseret Museum Bulletin,'' No. 2 (1911), 6-8. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044043476324</ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:02, 30 November 2017

The Michigan Relics (also known as the Soper Frauds) are a large grouping of pseudoarchaeological prehistoric artifacts "discovered" throughout the state of Michigan in the late nineteenth century. Many of the relics were inscribed with fraudulent hieroglyphs and cuneiform and were originally believed to be proof of pre-Columbian contact with the Americas.

The Michigan Relics

The first discovery of the relics in Michigan occurred in October 1890 when a man in Wyman, Montcalm County, Michigan found a small clay cup while digging post holes in a field. Shortly after that initial discovery in Wyman, many other more elaborate discoveries were made in a three or four mile diameter around Wyman. Most of the artifacts were authenticated by those who witnessed their discovery. The people of Montcalm County were digging anywhere from one to four feet into the surface undulations and mounds, and scores of "remarkable objects" were unearthed. [2] Among the objects uncovered were small caskets, tablets, ornaments, weapons, tools, smoking pipes, and pottery vessels made of copper and baked and unbaked clay of varying colors.

Daniel E. Soper & James Scotford

Daniel E. Soper was the Secretary of State for the State of Michigan in 1891 under Governor Edwin Winans. Soper was, however, replaced after a single year in office by Robert R. Blacker as Secretary of State.[3] Not much is known about Soper as a person, but there are conflicting accounts as to his reputation and character that have been published in accounts in relation to these "relics" that often bear his name.

James O. Scotford was a prominent digger ...

Pseudoarchaeology

With the rhetoric in which they were originally presented, the "relics" supported pseduoarchaeological narratives, primarily pre-Columbian contact. With their hieroglyphic inscriptions, the discoveries supported the idea that the state of Michigan and North American in general were inhabited, or visited, by European peoples before the existence of Native American tribes in the region. The inscriptions found on the clay and copper discoveries were tied to the the Egyptian, Greek, Assyrian, Phoenician, and Hebrew alphabets, thus providing evidence that a more advanced civilization existed in the region besides the Native Americans. The inscriptions were religions in nature thus proving that this advanced civilization had knowledge of the Old Testament. [5]

Debunking

Early debunkers of the Michigan Relics were academics who found problems with the discoveries very quickly. Professor F.W. Putnam, curator of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University from 1874 to 1909, was sent photographs of the discoveries. Professor Alfred Emerson, an archaeologist at Lake Forest College (later at Cornell University), reviewed the "relics" in June 1891. Following his visit, Emerson wrote "The articles were bad enough in the photograph... an examination proved them to be humbugs of the first water." Emerson continued in his writing pointing out the the flaws in the fradulent relics, among Emerson's specific observations were:

- The hieroglyphs were stamped cuneiform characters in random order.

- The figures on some of the discoveries included lions with no tails, an omission which would not have occurred by "primative" artists.

- The clay items were dried on a machine-sawed board.

- The objects disintegrated in water, indicating that they could not have been buried in the ground for very long.[7]

The University of Michigan & Professor Frank Kelsey

Professor Emerson's expert evaluation of the Michigan Relics was criticized and considered hasty by those who were promoting the finds. Following Emerson's visit, those involved with the relics contacted the University of Michigan for a second opinion. The University of Michigan sent Professor Francis W. Kelsey, archaeologist and professor of Latin and Literature, who was to be accompanied by a scholar from the Smithsonian Institution.

The Frauds Today

References

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 50-51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 48-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ "List of Michigan Secretaries of State." Michigan Department of State. Accessed November 22, 2017. http://www.michigan.gov/sos/0,4670,7-127-1640_9105_61239---,00.html.

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf

- ↑ Talmage, James Edward. "The Michigan Relics: A Story of Forgery and Deception." Deseret Museum Bulletin, No. 2 (1911), 6-8. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044043476324

- ↑ Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. https://www.flickr.com/photos/79736948@N02/26005683552/in/dateposted-public/

- ↑ Kelsey, Francis W., "Archaeological Forgeries from Michigan." American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1908), 49-51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/659777.pdf